WAPO – How far would the United States go to back Ukraine?

Quoted by Anthony Faiola Washington Post:

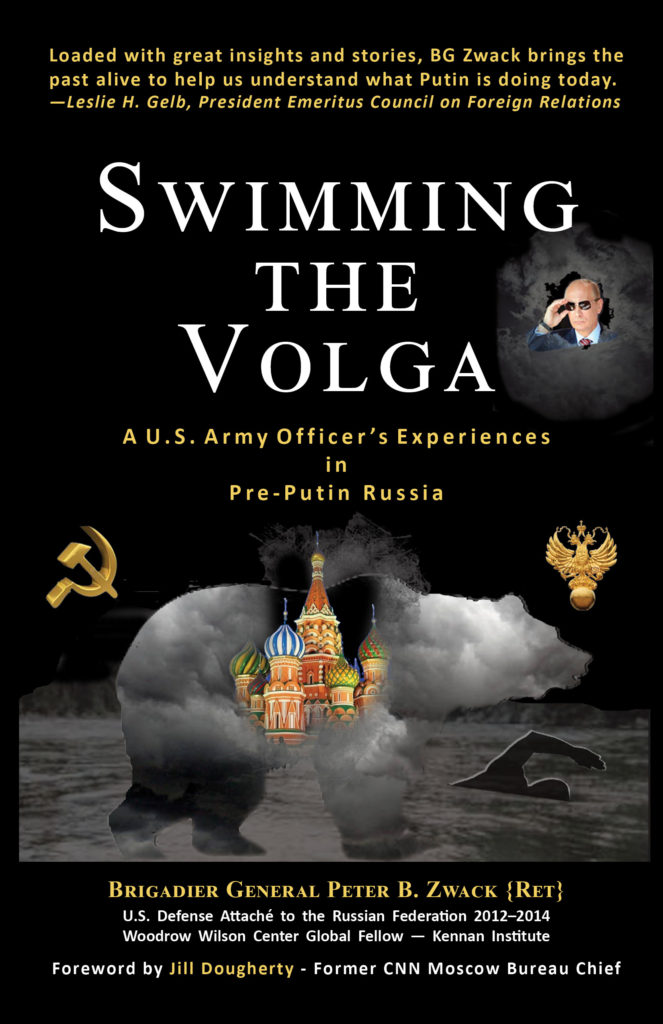

But a Russian invasion appears set to compel the West to send more, and broader, firepower: “I think that we’re talking about trying to take the edge or deter a Russian mostly conventional ground offensive,” Peter Zwack, former U.S. Army brigadier general and former defense attache to the Russian Federation, told NPR this week. “And for that, the Ukrainians would need more Javelin antitank missiles.”

They would need surface-to-air missiles such as Stingers, he said: “They need to be able to knock down, threaten Russian air support.”